Emerging Water-Energy-Minerals Nexus Stress: A Non-Obvious Inflection in Resource Scarcity

Resource scarcity discussions often treat water stress, critical mineral demand, and energy transition as parallel but mostly independent challenges. Yet, an under-recognized inflection is emerging within the next 10–20 years that tightly couples these resource systems, driven by industrial water demand—particularly from mining critical minerals—and constrained freshwater availability. This confluence may structurally reshape capital allocation, industrial strategy, and regulatory approaches by forcing an integrated water-energy-minerals nexus governance perspective.

Signal Identification

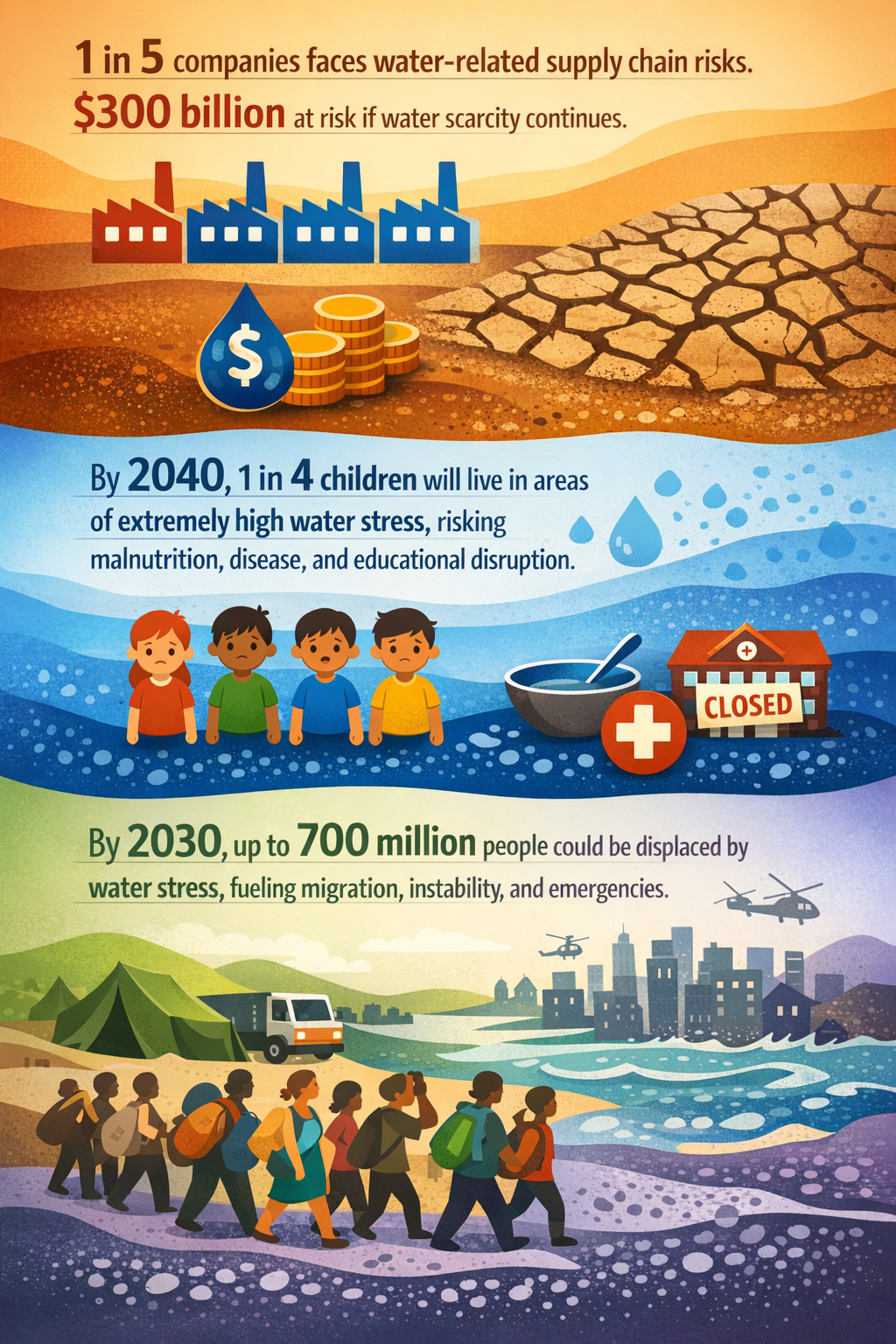

The signal qualifies as an emerging inflection indicator given the growing evidence of compound stresses linking critical mineral mining’s water consumption with intensifying water scarcity globally, especially in key mining regions like Africa and North America. Its plausibility is high for the 10–20 year horizon due to verified projections of quadrupling critical minerals demand by 2040, coinciding with rising water stress for one in four children globally by 2040. Sectors exposed include mining, water utilities, energy (notably nuclear and electricity transmission sectors), and regulatory governance related to natural resource licensing and environmental impact oversight.

What Is Changing

Multiple sources indicate a dramatic rise in demand for critical minerals essential to energy transition technologies and electric vehicles (EVs) (e.g., G7 talks emphasizing critical minerals realignment, African mining’s shifting centrality, requisite capital flows into exploration programs). This demand surge correlates with intensifying water scarcity, as mining operations are simultaneously large water consumers and contributors to water stress (Campo et al. 2023). Such water stress affects vulnerable populations, particularly children in regions of extreme water scarcity (projected by 2040), elevating social risk (Boston College Center for Corporate Citizenship, 2024).

Additionally, water reuse in mining is becoming increasingly critical, indicating emerging operational shifts but also signaling intensifying competition for limited freshwater. Countries heavily investing in critical minerals, such as Botswana and Canada (Manitoba exploration), face the dual challenge of scaling production while mitigating water impacts—a tension that may prompt regulatory tightening and compel industrial adaptation (Energy Capital Power, 2026; Hudbay Minerals, 2026).

The interdependence extends to energy systems. Projects led by energy infrastructure firms and development funds prioritize nuclear and power grid expansion, often to support mining and mineral refining facilities, creating feedback loops where energy security hinges on mineral supply chains that are water-intensive (Lexology on EDF activity, 2026). This water-energy-minerals nexus introduces a compound resource dependency rarely acknowledged in regulatory or capital planning frameworks today.

Disruption Pathway

This compounding resource interdependency may escalate from current operational challenges to systemic disruption as water scarcity amplifies operational costs and social license risks for mining, while energy projects requiring minerals face project delays or cost overruns due to water constraints. Increased water demand tied to critical minerals mining could provoke stricter environmental regulation, prompted in part by heightened water stress impacts on local communities, especially in emerging markets.

Escalating water stress stands as a direct cost multiplier for producers and could act as a critical failure point for supply chains. If mining regions fail to secure sustainable water supplies—through reuse or alternative sources—investors may reallocate capital toward jurisdictions with integrated water management policies or technological solutions addressing water in extraction processes. This could drive industrial consolidation around firms with advanced water stewardship and innovative processing capabilities.

Regulatory frameworks may evolve to embed water risk into mineral resource permitting and financing criteria, linking water use to mineral reserves valuation and project viability. This would shift industrial structure away from current fragmented resource governance toward cross-sector governance models incorporating water, energy, and mineral interdependencies. Over 10–20 years, such adaptation could alter dominant models for environmental impact assessment and infrastructure project financing on a global scale.

Why This Matters

Decision-makers should recognize this nexus stress because it creates a multi-resource bottleneck that may redefine competitive advantage, regulatory compliance, and sovereign risk. Capital allocation might increasingly exclude or devalue projects exposed to water scarcity or lacking robust water management strategies, influencing exploration and production geography. Regulatory bodies might extend scrutiny beyond traditional environmental impact into integrated water use and community resilience assessments.

Supply chains for EVs, renewable energy infrastructure, and advanced electronics depend on critical minerals whose production may no longer be separable from water security considerations, exposing downstream manufacturers and governments to compound supply and social governance risks. Liability regimes could evolve to hold mining and energy firms accountable for indirect impacts tied to water-related social disruption, further incentivizing integrated governance approaches.

Implications

This development may likely intensify capital shifts toward jurisdictions and technologies that explicitly address water-energy-minerals interdependence through innovation and governance. Regulatory frameworks could increasingly mandate integrated resource impact assessments and water usage caps or require more sophisticated water recycling metrics in critical mineral operations. Industrial players might increasingly adopt circular economy principles for minerals and water, alongside digital water management technologies.

This signal is distinct from generic ‘green transition’ narratives because it foregrounds water as a gating factor that could constrain or reshape mineral extraction rather than demand alone driving supply expansions. It also challenges assumptions of separable resource governance and isolated investment decisions. Competing interpretations might downplay water scarcity impacts by focusing on technological breakthroughs in desalination or alternative mineral sources, but these solutions face cost, energy, and environmental trade-offs that may not scale universally.

Early Indicators to Monitor

• Increased patent activity and venture funding in water recycling and treatment technologies specific to mining.

• Regulatory draft proposals integrating water use limitations into mining permits across major mineral producing countries.

• Clustering of critical minerals premium flow-through financing with explicit ESG (environmental, social, governance) criteria on water impact.

• Procurement shifts by EV and battery manufacturers favoring suppliers with verified water stewardship.

• Strategic announcements from governments aligning critical mineral policies with water resource management plans.

• Escalating community conflicts or litigation linked to water impacts in mining-intensive regions.

Disconfirming Signals

• Breakthrough deployment of cost-competitive, low-water mining technologies or miningless extraction methods that neutralize water demand.

• Large-scale recovery and recycling of critical minerals from urban mining or oceanic sources reducing the need for water-intensive primary mining.

• Successful decoupling of critical mineral production growth from water use demonstrated through widespread adoption of renewable energy-powered desalination for mining operations.

• Regulatory rollbacks or inertia maintaining separate governance siloes for water and minerals without integration.

• Substantial discovery of abundant critical mineral deposits in water-abundant regions reducing geographical water stress in supply chains.

Strategic Questions

- How does current capital allocation embed integrated water risk assessments in critical mineral projects?

- What mechanisms exist or should be developed to align water governance with critical mineral supply chain security?

- How can industrial and regulatory actors incentivize innovation in low-water-use mineral extraction techniques?

- In what ways could multi-resource nexus governance alter traditional permitting and environmental impact frameworks?

- Could reliance on specific jurisdictions facing escalating water stress create systemic bottlenecks in the clean energy transition?

- What strategies can reduce social license risks arising from mining-associated water scarcity in vulnerable communities?

- How can cross-sector collaboration between water utilities, mining companies, and energy providers be operationalized to manage compounded resource risks?

Keywords

Critical minerals; Water scarcity; Mining; Water reuse; Resource governance; Energy transition; Capital allocation; Supply chain; Environmental regulation; ESG.

Bibliography

- Boston College Center for Corporate Citizenship 2024

- Tetakawi Insights, USMCA 2026 Review 2026

- Discovery Alert, Strategic Supply Chain Transformation 2026

- Campo et al., Mining Water Use and Reuse 2023

- Hudbay Minerals 2026 Results

- Energy Capital Power, Botswana Critical Minerals 2026

- African Mining Week 2026 Priorities

- Lexology, EDF Energy Projects 2026